EXPLORE THE

LONG MARCH TO FREEDOM

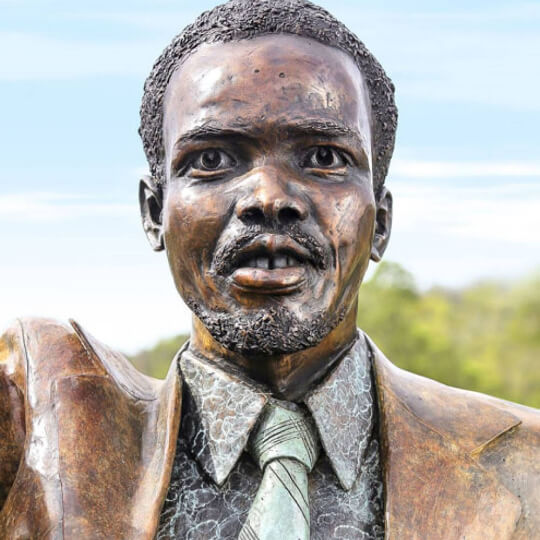

DALI TAMBO

WELCOME MESSAGE FROM THE CEO OF THE NATIONAL HERITAGE PROJECT NON-PROFIT COMPANY AND LONG MARCH TO FREEDOM

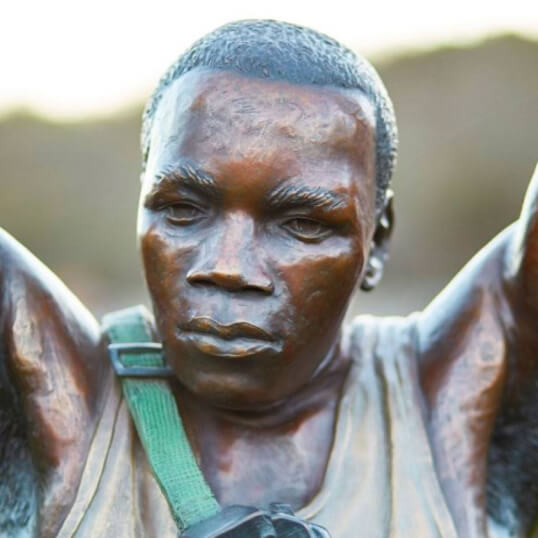

Welcome to Long March to Freedom, the world’s greatest exhibition in bronze, and South Africa’s most enticing heritage tourism attraction. A pantheon of 100 life-size bronze sculptures of liberation heroes honours South Africa’s brightest and bravest icons and tells the story of the country’s 350-year journey to freedom and democracy.

At the heart of meaningful tourism experiences lies integrity, depth, culture and heritage. South Africa's cultural and political heritage is one of the country’s most valuable assets. Our struggle was the moral cause of the international community and the greatest solidarity movement of the 20th Century and it is the duty of the generation that remembers to ensure that those who follow know of the efforts of legions of freedom fighters, know of our journey to democracy, and understand the sacrifices that allow us to have the society we do today.

People who visit our shores often say: 'We have seen the beauty of your landscapes and beaches, the majestic wildlife and more, but we still didn’t know you as a people. Where do we go to understand South Africa's journey to freedom?’ I believe this exhibition delivers that story, through the lives of the countless souls who never saw that freedom but ensured we would. The time will come when Long March to Freedom is a ‘must see’ heritage tourism attraction for foreign tourists, and South African’s will visit time and again, revelling in and humbled by this glorious statement of national pride. Here’s wishing you an inspiring and uplifting journey with us today.

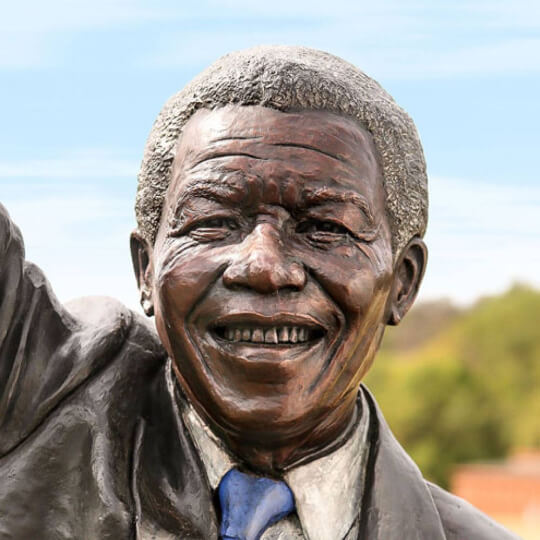

Walter Sisulu is seated with Nelson Mandela, his then-wife Winnie, and Sisulu’s wife Albertina at a rally to celebrate Mandela’s release from jail in 1990.

South Africa’s struggle for liberation was fought over three centuries of colonial domination and four decades of apartheid rule. In 1994 freedom was won and the world celebrated our new democracy with us.

Today we bring you the iconic leaders of this epic journey, from the first chiefs to the last activists, in The Long March to Freedom – a ground-breaking public attraction at the heart of the National Heritage Monument.

LONG MARCH TO FREEDOM:

A 350-YEAR JOURNEY TO LIBERATION (1652-1994)

Honour Them All

South Africa has an extraordinary history. It has been characterized by turbulence and transformation through complex forces of racialization, diversification, cultural violence, migration, displacement, industrialization, slavery, colonization, as well as radical political transformation. The interplay of these forces has punctuated the story of South Africa from its earliest inhabitants, through its turbulent inter-cultural and colonial encounters, into the post-apartheid era. At the heart of this sweeping narrative are the lives of individuals who, against great odds, faced these trials of history with courage, strength of purpose, rectitude and dignity. The Long March to Freedom honours these inspirational lives in a monumental bronze procession of achievement spanning 350 years.

First People

Modern humans have lived at the southern tip of Africa for more than 100 000 years and their ancestors for some 3,3 million years. Some 2 000 years ago, the Khoekhoen (Khoikhoi) were pastoralists who had settled mostly along the coast, while the San were hunter-gatherers spread across the region. At about the same time, Bantu-speaking agropastoralists from central and west Africa started arriving in what is now South Africa , and settled the eastern lowlands and the interior of the country (the Highveld). Their movement was probably driven at least in part by a search for new agricultural lands and iron ore sources. Several archaeological sites evidence the sophisticated political and material cultures of these communities.

The arrival of the Europeans

The first European settlement in southern Africa was established by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in Table Bay (Cape Town) in 1652. The Dutch were not the first Europeans to visit: Portuguese seafarers made landfall in the late 1400’s, interacting and trading with the Khoekhoen. Over the next century English, Scandinavian and French ships made stopovers at the Cape. The VOC settlement was created to supply passing ships with fresh produce, and the colony grew rapidly as Dutch farmers arrived to grow crops. Slaves were soon imported from East Africa, Madagascar, and the East Indies (mostly from what is today Indonesia and Malaysia). To establish the farms the Dutch appropriated the lands of the Khoekhoen who were forced into less fertile areas. Resisting this invasion the Khoekhoen embarked on a series of unsuccessful armed uprisings against the Dutch and within 100 years the indigenous communities around what is today Cape Town had been dispossessed of their lands and independent means of existence. In addition, many died of smallpox brought by Europeans or were assimilated into colonial society as servants.

Nommoä (Doman) Goringhaiqua (1618 - 1663)

Leader of the First Khoikhoi-Dutch War and interpreter to Dutch Cape Governor Jan van Riebeeck.

Autshumato (1625 – 1663)

Leader of the Goringhaikonas, interpreter, negotiator and rebel leader.

Expansion and Conflict

The Dutch settlement expanded: French Huguenot refugees arrived in 1689, after Calvinism was banned in their country, and numbers were further swelled by people from Germany, Scandinavia, Flanders, and Switzerland. Dutch livestock farmers – ‘trekboers’ (semi-migrant farmers – later the ‘Boers’) started moving beyond the borders of the colony and from the 1770s came into contact and inevitable conflict with isiXhosa-speaking peoples, some 800km east of Cape Town. The Xhosa kingdoms were themselves expanding their own territories along South Africa’s east coast. The intermittent clashes, historically known as the nine Frontier Wars, would continue for nearly one hundred years involving Xhosa, Boer, Khoekhoen, San, and (after 1795) the British. As had happened with the Khoekhoen the continuing colonial expansion would eventually dispossess the Xhosa of their herds and their land.

In 1795, the British seized the Cape as a strategic base against the French, controlling the sea route to the East, and permanently occupied it in 1806. Their greatest problem was the unrest on the eastern frontier as neither Boer nor Xhosa were prepared to submit quietly to British rule. In 1820 some 5 000 British settlers, known as the 1820 Settlers, arrived in Algoa Bay (now Nelson Mandela Bay). From all walks of life, they were settled along the turbulent eastern border of the colony, in what is now the Eastern Cape, to create a buffer between Xhosa and Boer, and also had the effect of denying the Boers the opportunity to set up a port on the eastern seaboard.

At the same time celebrated leader, King Shaka, oversaw the military, social, and kinship re-ordering of the Zulu Kingdom on the east coast of what is now KwaZulu-Natal, and established sway over a vast area of southern Africa. As splinter Zulu groups spread, conquered, and absorbed communities in their path, fundamental social disruption spread across the region. It was a nearly 40-year period of widespread conquest and warfare between the indigenous groups, known as the Mfecane (isiZulu) or Difaqane (Sesotho), both meaning ‘crushing, scattering, forced dispersal, and migration’. Substantial states, such as Moshoeshoe’s Lesotho and other Sotho-Tswana chiefdoms were established, and other groups such as the Matebele (later Ndebele), Mfengu, and Makololo were consolidated.

Chief David Stuurman (1773 – 1830)

Hero of the Khoena (Khoekhoen) Resistance

King Hintsa kaKhawuta of the House of Phalo (1789 – 1835)

Paramount chief of amaGcaleka and King of the Xhosa

King Moshoeshoe I (c 1786 – 1870)

Founding father and first King of the Basotho, Moshoeshoe I

Migration, Minerals and War

The British occupation prospered and throughout the 1800s the boundaries of European influence expanded to the east and north beyond the borders of the Cape. The British Colony of Natal was proclaimed in 1843. The Boers resented British rule and felt marginalised. They were further antagonised when slavery was abolished in 1834 and began a mass migration away from the Cape Colony, known as the Great Trek. They would finally establish two land-locked republics away from the British - the Orange Free State (current day Free State) and the South African Republic (current day Gauteng, Northwest, Limpopo, and Mpumalanga provinces).

The British recognized the Dutch-speaking Boer republics in the 1850’s, but the situation would change with the discovery of South Africa’s vast mineral wealth. Diamonds were found in 1867 in what is now the Northern Cape; however the real turning point was the discovery of gold in the South African Republic in 1886. English-speaking immigrants (called Uitlanders – foreigners – by the Boers) lured by the promise of riches on the goldfields streamed into the SAR and the demand for franchise rights for them was the pretext Britain employed to declare war on both Boer republics in 1899.

The Anglo-Boer War, or South African War, was the bloodiest, longest and most expensive war Britain engaged in between 1815 and 1915. It cost more than 200 million pounds and Britain lost more than 22 000 men. The Boers lost over 34 000 people, 20 000 of them women and children herded into British concentration camps. Black South Africans and even San people were inevitably affected by the ‘white-man’s war’ as the conflict raged over their lands. Many were pulled into participating in military operations on both sides, and some became involved in hostilities with the Boers, defending themselves or settling old scores. More than 15 000 black South Africans were killed. The war additionally inspired anti-British social movements across the empire, as far away as East Asia where Boxer rebels in China adopted pro-Boer slogans as rallying cries for their anti-European imperialist movement.

Chief Kgalusi Leboho (Maleboho) (1844 – 1939)

Chief of the Bahananwa and besieged prisoner of the Boers

Harriette Emily Colenso (1847 – 1932)

Opponent of British colonialism in Natal and first woman to give testimony before the British House of Commons

Union and Opposition

In 1902 the Peace Treaty of Vereeniging marked the end of the war and the defeat of the Boers – by now known as the Afrikaners. The black population saw the treaty as an opportunity to establish justice and equality for all ethnic groups, but this was not to be. No allowance was made for black franchise or parliamentary representation, and the journey towards full racial segregation continued. In 1910, the two British colonies and the two Boer republics were united into the Union of South Africa with centralised self-government under British supremacy. Black opposition led to the formation in 1912 of the South African Native National Congress, renamed in 1923 as the African National Congress (ANC). Over the following decades many more liberation struggle movements were formed, representing other ethnic groups, ideologies and civil societies.

The Natives Land Act of 1913 was the first major segregation legislation passed by the Union Parliament, restricting ownership of land by black people to a mere 13% of the Union. It was followed by a succession of race-based, increasingly draconian statutes all aimed at cementing the power of the white population and regulating and restricting every possible aspect of the lives of black, coloured, and Indian people. Black opposition politics, in the meantime, were consolidating. In 1944, a younger, more determined and militant political group - the ANC Youth League – was launched, an organisation which would foster the leadership of people such as Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, Oliver Tambo and Walter Sisulu.

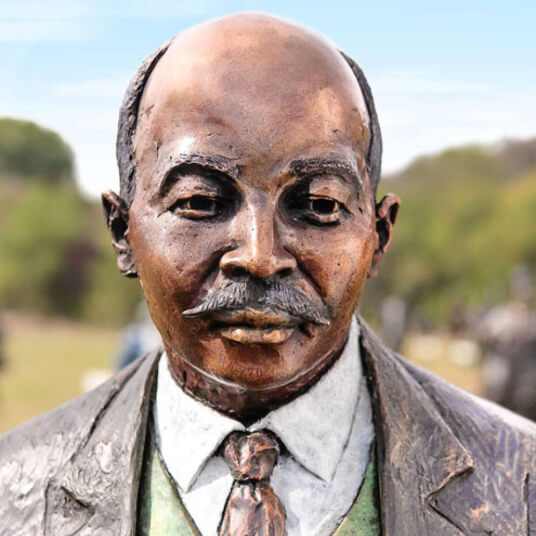

John Langalibalele Dube (1871 – 1946)

First President General of the South African Native National Congress

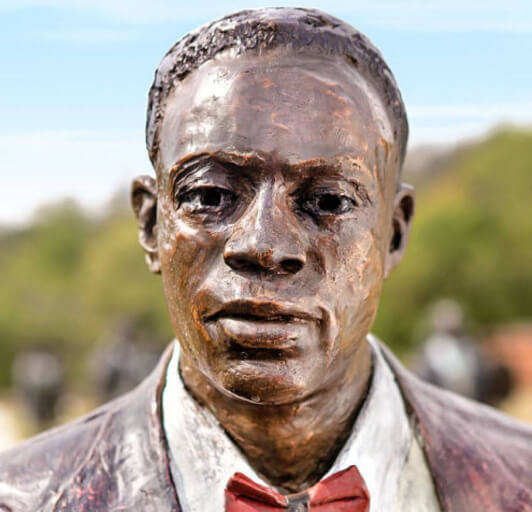

Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje (1876 – 1932)

Founding member and first Secretary General of the South African Native National Congress, journalist and author

Alfred Mangena (c 1879 – 1924)

Founding Member and one of four Deputy Presidents of the South African Native National Congress

Apartheid and Resistance

In 1948, the pro-Afrikaner National Party came to power with the ideology of apartheid, an even more formalised, rigorous and authoritarian approach than any previous segregationist policies. At a time when much of Africa was on the verge of independence from colonial powers, the South African Government was strengthening its policy of separate development.

The Black population was divided into artificial ethnic ‘nations’, each with its own ‘homeland’ and the prospect of ‘independence’. Forced removals from areas designated for Whites affected millions of people, and the homelands became vast rural slums. The ANC adopted its Programme of Action, expressing the renewed militancy of the 1940s, and embodying a rejection of white domination and a call for action in the form of protests, strikes and demonstrations, This would eventually lead to the Defiance Campaign of the 1950s against discrimination in all forms, especially the ‘unjust laws which keep in perpetual subjection vast sections of the population.

The Defiance Campaign carried mass mobilisation to new heights under the banner of non-violent, passive resistance and in 1955 the Freedom Charter was drawn up and adopted at the Congress of the People in Kliptown, Soweto. The charter enunciated the principles of the struggle, binding the liberation movements to a culture of human rights and non-racialism. In 1956 thousands of women joined the Women’s March to the Union Buildings in Pretoria to protest against the infamous pass laws.

The State responded swiftly and brutally to all the protests and many thousands were arrested, imprisoned or subjected to banning and restriction orders, all of which would culminate in the 1956 Treason Trial.

Lilian Ngoyi (1911 – 1980)

President of the African National Congress Women’s League, President of the Federation of South African Women and leader of the 1956 Women’s March

Helen Joseph (1905 – 1992)

Founding member of the South African Congress of Democrats, founding member of the Federation of South African Women and co-leader of the 1956 Women’s March

Rahima Moosa (1922 – 1993)

Co-leader of the 1956 Women’s March, Union Activist, member of the Transvaal Indian Congress, and organiser of the Congress of the People

Repression and Armed Struggle

The Treason Trial dragged on for 5 years and the 156 accused were eventually acquitted. It did however elicit the first real condemnation from the global community on what was happening in South Africa. In March 1960, police opened fire on peaceful Pan-African Congress protestors in Sharpeville, in what is now Gauteng, sixty nine of whom were killed. The Sharpeville Massacre made world headlines and South Africa started to slide into isolation.

The apartheid government responded by imposing a state of emergency, introducing detention without trial, and banning the liberation organisations, including the ANC and the Pan-Africanist Congress, forcing them underground. Their policies of passive resistance had been met by violence and repression from the state, and the only remaining option was armed struggle.

In October 1960, the National Party Government broke with the British Commonwealth and declared South Africa a republic after winning a whites-only referendum. Leaders of the black political organisations not yet arrested were in hiding, or had left the country as exiles.

The ANC established external missions in sympathetic African states and in London, led for the next 30 years by Oliver Tambo. In 1961, secreted in a safe house in Rivonia, Johannesburg Nelson Mandela and activists from the ANC, the South African Communist Party and other organisations, formed the ANC’s armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK - Spear of the Nation) aiming to sabotage government targets.

In 1963 state security forces swooped on the hideout and arrested almost the entire MK leadership and the ensuing Rivonia Trial would see them sentenced to life imprisonment on Robben Island. The state regarded the resistance movements as well and truly crushed and the for the next ten years there was little protest action within the country itself.

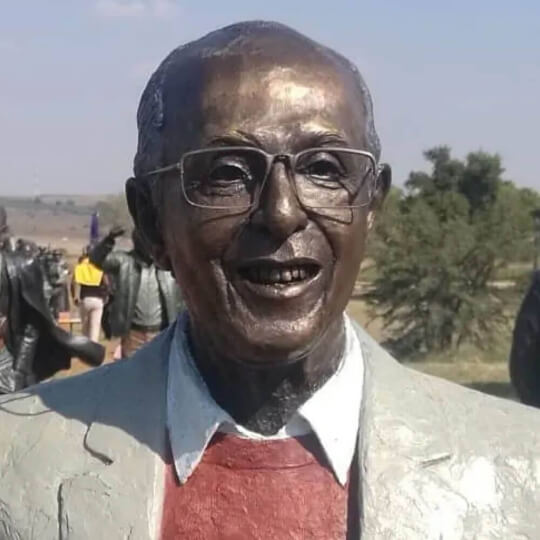

Ahmed Kathrada (1929 – 2017)

Anti-Apartheid & Social Justice Activist, Rivonia Trialist and Robben Island prisoner

Robert Sobukwe (1924 – 1978)

President of the Pan Africanist Congress

Bram Fischer (1908 – 1975)

Afrikaner Revolutionary, Lawyer, South African Communist Party Leader, Member of the Congress of Democrats, Political Prisoner

Resurgence of Resistance Politics

The resurgence of resistance politics in the 1970s was dramatic. On 16 June 1976 mass uprisings began in Soweto as school pupils protested against the ‘Bantu Education System’ and the imposition of learning in Afrikaans, the language of the oppressor. Police reacted with force, often firing live rounds into the crowds of children, and many lost their lives. The uprisings spread quickly and marked the beginning of a sustained anti-apartheid revolt as many concerned observers across the world reacted with horror and condemnation toward the apartheid government following its brutal suppressions and violent political reprisals – many targeting political figures and institutions beyond the country’s borders. As a result, economic sanctions against South Africa intensified and increased.

New resistance movements soon emerged. The non-racial United Democratic Front pursued a non-violent strategy known as "ungovernability" including rent boycotts, student protests, and strike campaigns. The UDF was replaced in 1988 by the Mass Democratic Movement, a loose and amorphous alliance of anti-apartheid groups that had no permanent structure, making it difficult for the government to place a ban on its activities. Grass-roots anti-apartheid movements, inspired by the black-consciousness teachings and writings of individuals such as Steve Biko and Robert Sobukwe, offered new hope for a younger generation of activists. A total of 130 political prisoners were hanged on the gallows of Pretoria Central Prison between 1960 and 1990. The prisoners were mainly members of the Pan Africanist Congress and United Democratic Front.

Steve Biko (1946 – 1977)

Co-founder of the Black People's Convention and leader of the Black Consciousness Movement

Solomon Mahlangu (1956 – 1979)

uMkhonto weSizwe cadre and youth activist

Reform and the Last Days of Apartheid

Shaken by the scale of protest and opposition, and increasing international support for the anti-apartheid cause, the apartheid government embarked on a series of limited reforms in the early 1980s. In 1983, the constitution was amended to allow the Coloured and Indian minorities some limited participation in separate and subordinate houses of parliament. In 1986 the pass laws were scrapped. Mass resistance increasingly challenged the apartheid state, which resorted to intensified repression accompanied by an eventual recognition that apartheid could not be sustained.

By this time, many among the Afrikaner élite openly started to pronounce in favour of a more inclusive society, with a number of business people, students and academic leaders meeting publicly and privately with the ANC in exile. Petty apartheid laws and symbols were openly challenged and eventually removed. Protracted military conflicts on the borders of the country, sustained underground resistance to the apartheid system, a severely ailing economy, increasing public dissent, and international pressure eventually led to the fall of apartheid. On 2 February 1990 then Prime Minister Willem de Klerk announced the unbanning of the liberation movements and the release of Nelson Mandela and all other political prisoners.

Chris Hani (1942 – 1993)

General Secretary of the South African Communist Party

Winnie Madikizela Mandela (1936 - 2018)

Anti-Apartheid and Human Right activist and leader

Towards a New Democracy

On 11 February 1990 Nelson Mandela walked free after 27 years imprisonment. From the balcony of the Cape Town City Hall, he repeated his words from the 1964 Rivonia Trial when he was sentenced to life imprisonment: ‘I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the idea of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.’ In the period that followed, mass meetings and mobilisations, strikes, protests, demonstrations and violence ushered in profound uncertainty and potentially dangerous instability in the country.

The ANC, National Party Government and other political organisations committed to resolving the violence and intimidation, and removing obstacles to negotiations. In 1991 the National Peace Accord was signed, paving the way for the Convention for a Democratic South Africa – CODESA – which commenced in December of that year. In a 1992 whites-only referendum indicated that more than two-thirds of white voters favoured the negotiations for a democratic constitution, but talks broke down later that year over the primary concerns of majority rule and power sharing. Mass action campaigns and violence soon erupted. At Boipatong in the Vaal Triangle 45 people were massacred in a factional attack, and at Bisho in the Ciskei homeland (now Eastern Cape) 28 ANC supporters were gunned down by the Ciskei defence force. Behind-the-scenes meetings later in 1992 between government representative Roelf Meyer and the ANC's Cyril Ramaphosa managed to get negotiations back on track, leading to the Multi-Party Negotiating Forum (MPNF) in April 1993, which included greater participation from parties on the extreme right and left of the political spectrum.

Proceedings at the MPNF did not run smoothly. The mainly Zulu Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), claiming they were being side-lined, pulled out and formed the Concerned South Africans Group together with traditional leaders, homeland leaders, and white right-wing groups. A period of brinkmanship followed, with the IFP remaining out of the negotiations until within days of the election in 1994.

On 10 April 1993 the assassination by white right-wingers of Communist Party and ANC leader, Chris Hani, brought the country again to the brink of disaster. Nelson Mandela appealed to black and white South Africans to stand together against “the men who worship war” and to “move forward to what is the only lasting solution for our country – an elected government of the people, by the people and for the people”. It would prove a turning point, after which the main parties pushed for a settlement with increased determination. The MPNF ratified the interim Constitution in the early hours of the morning of 18 November 1993.

On 27 April 1994 millions of South Africans of all races stood together peacefully for hours in kilometre-long queues to make their mark at the polls. For most it was the first time that they or any of their forbears had been able to vote or indeed have any say on how their country should be governed. The ANC won 62% of the vote and on 10 May 1994 Nelson Mandela was sworn in a South Africa’s first democratically elected president. Under the Government of National Unity (GNU), South Africa was divided into today’s nine provinces, replacing the four pre-existing provinces and 10 black homelands. The GNU additionally oversaw the drafting of a new constitution which came into effect in 1997, and is still regarded as one of the most progressive in the world today.

Nelson Mandela (1918 - 2013)

South Africa‘s first democratically elected President, President of the ANC and Nobel Peace Prize winner

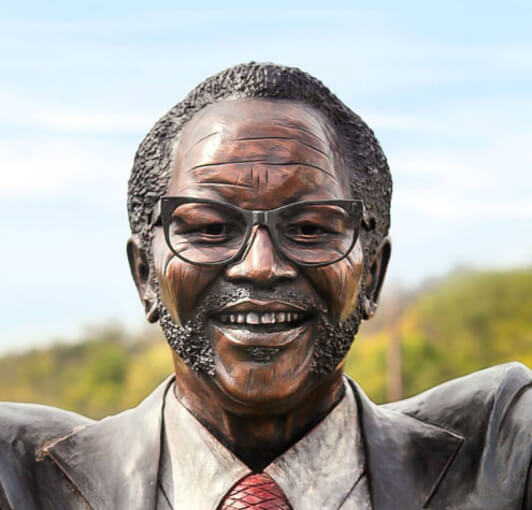

Oliver Reginald Tambo (1917 - 1993)

Longest-serving President of the ANC, and leader of the organisation in exile

Walter Ulyate Max Sisulu (1912 - 2003)

Anti-apartheid activist and political leader, Rivonia Trialist and Robben Island prisoner

EXPLORE THE

LONG MARCH TO FREEDOM

Get in touch with us to book a tour or request additional information. We usually respond within 24 hours.

Email Address

info@longmarchtofreedom.co.za

Physical Address

Century Boulevard, Century City, Cape Town, 7441

opposite the Shell Garage, Canal Walk Entrance 4