"It's nonsense to talk of my threatening - where is my power? Except in being in the right."

- Harriette Colenso's response when she was charged with threatening those responsible for good governance in Natal, 1897

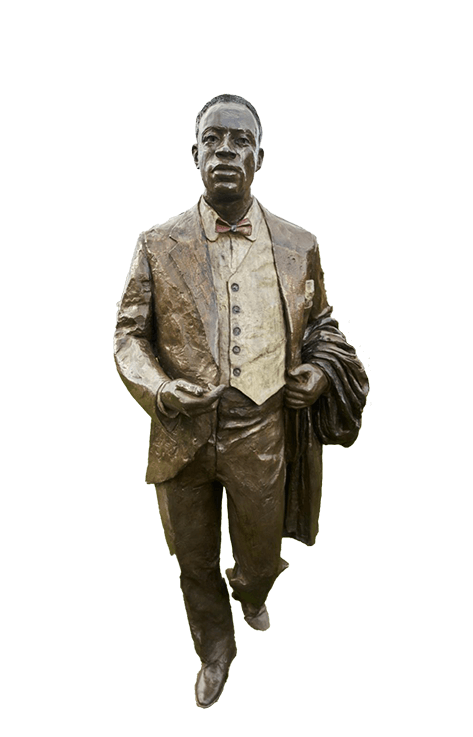

Harriette Emily Colenso

1847 – 1932

Opponent of British colonialism in Natal, First woman to give testimony before the British House of Commons

Harriette Colenso was born in Norfolk, England, the eldest of five children of the controversial Bishop John Colenso of Natal. She grew up at the Bishopstowe mission station close to Pietermaritzburg.

As a young girl she was known as Udhlwedhlwe, her father's 'Walking Stick', because of the help she gave him, both in his political as well as his religious work. Her command of Zulu exceeded his, and because of this linguistic prowess and keen interest in the political crises of her time, she served as a crucial ally of her father's during his lifetime. Even after his death she continued to fight for her father's renegade branch of the Church of England in Natal and for the political sovereignty of Cetshwayo's kingdom against colonial encroachment.

Her father had supported the Zulu king, Cetshwayo kaMpande, both before and after his defeat in 1879, while she in turn supported his son and successor, King Dinuzulu, in his attempts to regain his kingdom. She campaigned for him when the British government tried him in 1888. She became the first woman to give testimony before the British House of Commons when she spoke on Dinuzulus behalf. When he was again arrested and charged for alleged involvement in the Anti-Poll Tax Rebellion led by Bhambatha in 1906, she played a central role in leading his defence.

The founding members of the South African Native National Congress, later renamed the African National Congress in 1923, were friends of Harriete Colenso. Sol Plaatje, Pixley ka Seme and John Langalibalele Dube all feature in her correspondence and diary. Sol Plaatje dedicated his book Native Life in South Africa to her, in recognition of her 'unselfish interest in the welfare of the South African Natives'.

Although the average Natal colonist regarded her as fanatically prejudiced, even the local Natal Witness, the mouthpiece of colonial views, was forced to acknowledge her 'personal and intellectual qualities' and praised her acute understanding of the law, saying 'her grasp of the intricate points of trials and cases in which natives have been involved has often astonished able and experienced lawyers'.

Committed to justice within an increasingly unjust imperial environment, she became very unpopular among Whites in the colony for her strong public views. Nonetheless her role as a mediator representing the interests of the Africans in Natal sustained alliances across lines of race, gender and nationality during a volatile time in the making of modern South Africa.

Her political activities tapered off after Dinuzulu's death in 1913, though her missionary work continued until her own death in 1932.