"For my own part, I am deeply conscious of the added responsibility which the award entails. I have the feeling that I have been made answerable for the future of the people of South Africa, for if there is no peace for the majority of them, there is no peace for any."

– Albert Luthuli’s Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, Oslo, Norway, 10 December 1961

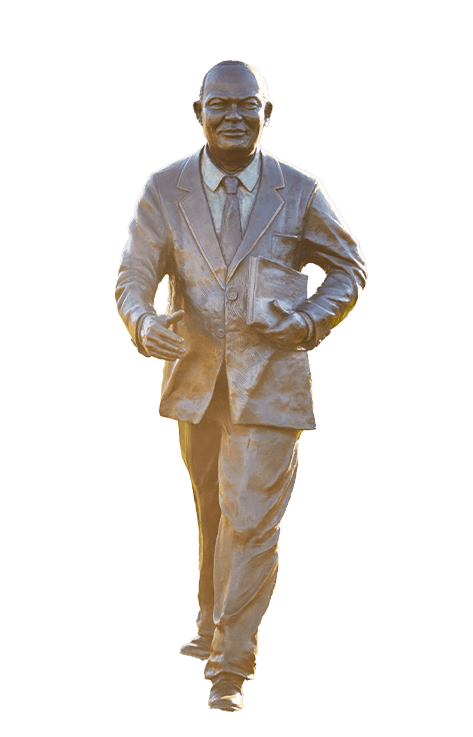

Chief Albert John Mvumbi Luthuli

1898 - 1967

President General of the ANC, Chief of the Abasemakholweni Zulu, Africa's first Nobel Peace Prize Laureate

Albert Luthuli was born in a Seventh Day Adventist mission near Bulawayo in present-day Zimbabwe.

His father died shortly after his birth and in 1908 the family returned to their ancestral home in Groutville, KwaDukuza on the north coast of Kwa-Zulu Natal. He started his school career at a nearby mission school and later studied at the Ohlange Institute, founded by John Dube, the first president of the South African Native National Congress.

He later trained as a teacher in Edendale, near Pietermaritzburg, and in 1922 became the first African to be employed on the teaching staff at Adam's College, the second oldest institution offering tuition to Africans and the first college to offer the matric syllabus in the province of Natal.

In 1936 Luthuli was elected chief by the Abasemakholweni (Christian converts) Zulu people. For seventeen years in Groutville, he presided at the tribal councils, bringing order into the sugar fields and increasing their yields, settling disputes, exacting fines and enforcing prevailing laws.

At the same time he strengthened his connection with organized Christianity, attending various international conferences and serving as chair of the Congregationalist Churches of the American Board in South Africa, as President of the Natal Mission Conference and as an Executive Member of the Christian Council.

His Christian beliefs laid a foundation for his approach to political life in South Africa at a time when many of his contemporaries were calling for a more militant response to the government's unjust racial laws.

He joined the African National Congress (ANC) in 1944 and was elected Natal provincial president in 1951, bringing to it the support of the rural conservatives previously distrustful of the young urban intelligentsia.

In 1952 Luthuli was one of the leaders behind the Defiance Campaign, a non-violent campaign targeting six unjust laws. In 1953 the apartheid government gave him the choice of renouncing his membership of the ANC or losing his position as Chief of the Reserve. Luthuli refused to resign, issued a press statement reaffirming his belief in non-violent resistance to apartheid, and was dismissed from the chieftaincy by the Native Affairs Department of the racist regime. That same year he was elected president general of the ANC by a large majority, with Nelson Mandela as deputy president.

The government responded by banning Luthuli, Mandela and nearly 100 others.

In 1956 Luthuli was among 156 people arrested and charged with treason. He was released but repeated bannings caused difficulties for the leadership of the ANC. Nonetheless, he was re-elected president general in 1955 and 1958.

In 1960, following the Sharpeville Massacre, Luthuli called for national stay-at-home strike to protest the regime's inhumane actions by publicly burning his pass book. Along with 18,000 others he was detained under the government's State of Emergency and was later confined to his home in Groutville under the Suppression of Communism Act, banned from receiving visitors, issuing statements or even attending church services.

In 1961 Chief Albert Luthuli was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his leadership role in the struggle. In 1962 he was elected Rector of Glasgow University, an honorary position, and the following year published his autobiography, Let My People Go.

Although suffering from ill health and failing eyesight, and restricted to his home in Groutville, Albert Luthuli remained president general of the ANC until his death.

On 21 July 1967, while out walking near his home, Luthuli was hit by a train and died. He was supposedly crossing the line at the time - an explanation dismissed by many of his followers who believed more sinister forces were at work.